Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle -- Women's Rights

... the woman question, even in those dark days, was not all black. Women of the upper classes mightsometimes be forlorn, but they were not bereft of influence-even on  their husbands. Women of the lower classes were often oppressed and exploited, but they did their best to join the oppressing and exploiting classes, and sometimes succeeded. The woman question continues debatable, its aspects changing according to point of viewand subjective interpretation. Among the upper classes, like a modern sovereign, the wife does not govern, but she often rules within the limits of rules that have been made by others. She has no power but can bestow honor, friendship, social acceptance, and standing. Among the lower orders the man rules, but the wife often governs, as mistress of the household, of the family budget, and of the cash-if she can get her hands on it.

their husbands. Women of the lower classes were often oppressed and exploited, but they did their best to join the oppressing and exploiting classes, and sometimes succeeded. The woman question continues debatable, its aspects changing according to point of viewand subjective interpretation. Among the upper classes, like a modern sovereign, the wife does not govern, but she often rules within the limits of rules that have been made by others. She has no power but can bestow honor, friendship, social acceptance, and standing. Among the lower orders the man rules, but the wife often governs, as mistress of the household, of the family budget, and of the cash-if she can get her hands on it.

I am inclined to believe that, among the better-off, the proportion of scatterbrains and vacuous flibbertigibbets was high, higher than it need have been. But, then, they had been deliberately bred to it, like the pretty goose of noble Lorraine blood whom Captain Esterhazy of Dreyfus fame [Esterhazy is now know to have been the cuprit in the espionage that Alfred Dreyfus was accused of committing. We will deal with this crucial case in Day 8]married in 1886, whose vapid snobbery and propensity to ennui provided some small retribution for his sinister excesses. The education inflicted in the convents and private schools to which the daughters of good families were condemned left many girls unable to carry on an intelligent conversation and deepened the intellectual gap between the sexes which the eighteenth century had begun to close. No well-bred girl would be allowed to read a novel or go to the theater without parental censorship; few could go out at all without some kind of chaperone. Marriage came as emancipation, but by then the harm had been done. Men and women who dined at the same table, separated after dinner. Men and women of social orders where this did not obtain, similarly divided into the separate worlds of kitchen and cabaret, lavoir and blacksmith's shop.

As long as maternity and household chores designated a woman's particular sphere, a degree of division was not unnatural. But education and social conditioning conspired to emphasize the difference, which increased in a vicious spiral. Defined as mindless, too many women were trained to mindlessness. Their menfolk, discouraged and equally conditioned, fled from their mindlessness instead of attempting to change it. The only men who did not flee were priests, who offered women attention and a sphere of activity denied them almost everywhere else-- a proclivity that further increased the division between the sexes.

The impression that, as Steven Hause and Anne Kenney put it, "attendance at Mass was a secondary sexual characteristic of French women" would have unfortunate effects on their political fortunes. Parliamentary majorities, however much they disagreed on other things, continued to believe that giving women the vote was tantamount to handing the country over to a retrograde Church. This left the women at the mercy of the Roman Law and of its 1804 incarnation, the Napoleonic Code, than which (at least from women's point of view) few churches could have been more retrograde. The Code treated women as minors. They were denied the vote, could not witness civil acts, serve on juries, take a job, or spend their own money without their husband's consent. Their adultery was treated as a crime, whereas husbands' adultery was not even a misdemeanor. At last, in 1903, one eccentric magistrate refused to find a woman who had left a brutal and alcoholic husband to live with a decent man guilty of adultery, despite a law which the judge denounced as anachronistic and unjust. But he was an exception.

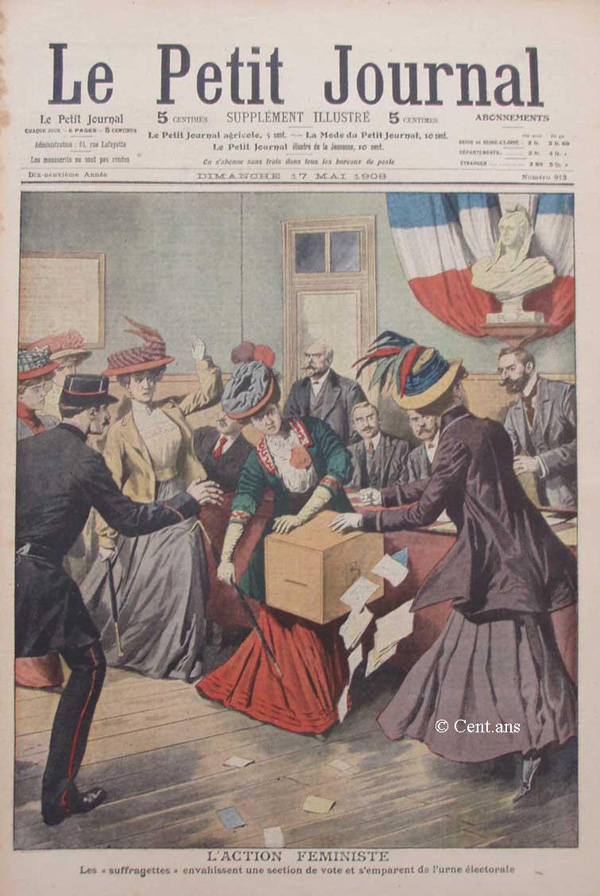

Because, in René Viviani's wise words, legislators make the laws for those who make the legislators, the women's suffrage movement was caught in a bind. Without a vote they could exert little pressure on legislators, and legislators would not give them the vote. French feminist and suffragist traditions went back a long way. But their adherents were few and divided and almost all of them were to be found in Paris. That was bad, but ambient prejudice was worse. Discussing women's rights, the widely read Petit Journal (May 3, 1897) compared the horrid circumstances obtaining in Colorado, where women were free to vote, to sit on juries, and allegedly to serve in the National Guard, with those in France where women were wives and mothers first of all, honored for it and enjoying the men's protection, even against themselves. The Petit Journal's readers were invited to look on the women of Colorado as Spartans did upon the drunken helot: as a horrid example that would remind them of the order and common sense they enjoyed at home.

A suffrage bill introduced in 1901 by an obscure deputy was never heard of again. And when, in October 1904, the feminists organized to heckle government celebrations of the hundredth anniversary of the Napoleonic Code, their feeble demonstrations flopped. Characteristically, the manifestation that drew most attention occurred during a ceremony at the Sorbonne, when Caroline Kauffmann interrupted the dignified proceedings by shouting "Down with the Napoleonic Code," while her hired man inflated and released balloons into the auditorium. This sort of thing was not calculated to make a deep impression, either on the general public or on the police court magistrate who dismissed her case.

Nevertheless, spasmodic legislative initiatives were chipping away at the Code. In 1884 divorce had been made possible though difficult; in 1886 women were enabled to open savings accounts without their husbands' consent; in 1893 single or separated women were granted full legal capacity; in 1897 all women were recognized as eligible witnesses in civil actions. That same year married women were allowed to dispose freely of their own earnings, and even to seize the husband's pay if his contributions to the household were deemed insufficient. They would shortly gain the right to initiate suits concerning family property and to be consulted on property sales. Though all this may read like a meager harvest, clearly things were looking up.